Migration of my website and blog

My website and blog have now been migrated to my own domain https://www.jrvarma.in/. Earlier, they were hosted at my Institute's website at https://www.iima.ac.in/~jrvarma/ and https://faculty.iima.ac.in/~jrvarma/.

My blog has been suspended for some time and is likely to remain suspended till October 2024. However, all old blog posts (along with the comments) have been migrated to the new location (https://www.jrvarma.in/blog/). There is also an rss feed and an atom feed, though these will be useful only when the blog resumes.

There is no change in the WordPress mirror https://jrvarma.wordpress.com/, and so those who were following my blog at WordPress can ignore this migration.

Posted at 1:20 pm IST on Mon, 14 Nov 2022 permanent link

Revisiting Jensen’s Agency Costs of Overvalued Equity

After the dot com bust, Michael C. Jensen wrote a paper comparing overvalued equity to managerial heroin:

When a firm’s equity becomes substantially overvalued it sets in motion a set of organizational forces that are extremely difficult to manage — forces that almost inevitably lead to destruction of part or all of the core value of the firm. (Jensen, M.C., 2005. Agency costs of overvalued equity. Financial management, 34(1), pp.5-19.)

What is amazing about the equity overvaluation created by meme-based investing (the reddit and Robinhood retail investors) is that far from destroying companies, it is resuscitating companies that were earlier presumed to be beyond salvation. On Tuesday, AMC Entertainment Holdings, Inc. raised $230 million by selling 1.7% of its equity to a hedge fund, Mudrick Capital, which promptly turned around and sold the shares into the market at a profit. AMC which claims to be “the largest movie exhibition company in the United States, the largest in Europe and the largest throughout the world with approximately 950 theatres and 10,500 screens across the globe” was struggling because of the pandemic and had plenty of uses for the money: it stated that:

The cash proceeds from this share sale primarily will be used for the pursuit of value creating acquisitions of additional theatre leases, as well as investments to enhance the consumer appeal of AMC’s existing theatres. In addition, with these funds in hand, AMC intends to continue exploring deleveraging opportunities.

With our increased liquidity, an increasingly vaccinated population and the imminent release of blockbuster new movie titles, it is time for AMC to go on the offense again.

The prospectus related to this sale described the risks very clearly:

it is very difficult to predict when theatre attendance levels will normalize, which we expect will depend on the widespread availability and use of effective vaccines for the coronavirus. However, our current cash burn rates are not sustainable.

during 2021 to date, the market price of our Class A common stock has fluctuated from an intra-day low of $1.91 per share on January 5, 2021 to an intra-day high on the NYSE of $36.72 on May 28, 2021 and the last reported sale price of our Class A common stock on the NYSE on May 28, 2021, was $26.12 per share.

the market price of our Class A common stock has experienced and may continue to experience rapid and substantial increases or decreases unrelated to our operating performance or prospects, or macro or industry fundamentals, and substantial increases may be significantly inconsistent with the risks and uncertainties that we continue to face; our market capitalization, as implied by various trading prices, currently reflects valuations that diverge significantly from those seen prior to recent volatility and that are significantly higher than our market capitalization immediately prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and to the extent these valuations reflect trading dynamics unrelated to our financial performance or prospects, purchasers of our Class A common stock could incur substantial losses if there are declines in market prices driven by a return to earlier valuations;

AMC shares rose after this capital raise, and AMC followed up on Thursday with a at-the-market offering of an additional 2.3% of its shares that raised $587 million at a price of $50.85 per share. The prospectus came with an even more blunt disclosure:

We believe that the recent volatility and our current market prices reflect market and trading dynamics unrelated to our underlying business, or macro or industry fundamentals, and we do not know how long these dynamics will last. Under the circumstances, we caution you against investing in our Class A common stock, unless you are prepared to incur the risk of losing all or a substantial portion of your investment.

Michael Jensen considered the possibility that capital raising could eliminate overvaluation, but ruled it out:

Some suggest that one solution to the problem of overvalued equity is for the firm to issue overpriced equity and pay out the proceeds to current shareholders. I have grave doubts that this is a sensible or even workable solution for several reasons.

AMC has shown that Jensen’s fears about regulatory obstacles and disclosure requirements were totally misplaced. But Jensen also raised an ethical issue which goes to the very foundations of corporate finance:

I believe it is impossible to create a system with integrity that is based on the proposition that it is ok to exploit future shareholders to benefit current shareholders. I realize this is not a generally accepted proposition in today’s finance profession, not even among scholars, but it would take us too far from my topic today to discuss it thoroughly.

I am not however impressed by this ethical argument because capitalism depends on allowing trades between two parties with differing beliefs and expectations without worrying that one party is mistaken and is therefore being exploited by the other. I see the AMC capital raises as capitalism working nicely to harmonize heterogeneous beliefs and expectations through the mechanism of mutually beneficial trades.

Posted at 4:07 pm IST on Fri, 4 Jun 2021 permanent link

Lessons from the Hertz Bankruptcy for Indian Bankruptcy Law

The pandemic induced Hertz bankruptcy in the US has upended a whole lot of what we thought we knew about how to run a bankruptcy proceeding.

What we used to think

It is optimal to complete the bankruptcy as quickly as possible. An insolvent business is like a melting ice cube that would lose all value if the bankruptcy were not sorted out very quickly. The gold standard of this approach was the Lehman bankruptcy in which the judge approved a sale agreement (filled with handwritten corrections) after midnight at the end of a chaotic day-long hearing. In India, the law mandates tight deadlines for the whole process, but it has not proved possible to adhere to them.

The big players know best and everybody else is basically a nuisance. In India, this is written into the law where a bunch of supposedly omniscient and incorruptible “financial creditors” have complete control over the proceedings and everybody else is left to their mercy (I have blogged about this here, here, and here). In the US, this is thankfully only an unwritten law, but there is little doubt that the big distressed debt investors are in charge.

The Absolute Priority Rule (APR) is the ideal way to distribute value: the sale proceeds or liquidation value should be distributed to creditors in the order of their seniority. This implies that the junior creditors as well as the shareholders often get wiped out. Bankruptcy courts do find ways to bypass the APR, but, to a first approximation, it more or less determines the allocation of value. In India, the APR is twisted to prioritize financial creditors over operational creditors, but in that modified form, it holds sway.

What Hertz taught us

Hertz reminds us that there are many exceptions to the received wisdom that guides our thinking and statutes about bankruptcy.

Hertz is likely to realize substantial value only because the bankruptcy court has run the proceedings at a leisurely pace allowing a sequence of ever higher bids to emerge as the pandemic abated. In some ways, this was an accident caused by the unplanned bankruptcy filing that was not accompanied by a Debtor in Possession (DIP) financing package, but it is at least partly due to the incessant prodding by the shareholders’ committee.

The retail shareholders who bought Hertz stock after it filed for bankruptcy were ridiculed at the time, but they now seem to have been at least partly right. The latest bids show that the shareholders will get some payout in bankruptcy after all. Some commentators have even compared the retail shareholders’ optimism to Bill Ackman’s legendary exploits during the General Growth Properties (GGP) bankruptcy.

Some scholars are now arguing that the Hertz bankruptcy exposes problems with the Absolute Priority Rule and that a Relative Priority Rule makes more sense. Casey and Macey argue that the option value of junior creditors and shareholders should not be extinguished as in the APR, but they should be allowed to recover that value as a payout in the bankruptcy proceeding, a stake in the reorganized firm, or a warrant that allows them to buy shares of the reorganized firm at a predetermined exercise price at a future date (see Casey, A.J. and Macey, J.C., 2020. The Hertz Maneuver (and the Limits of Bankruptcy Law). U. Chi. L. Rev. Online, p.1. available at https://lawreviewblog.uchicago.edu/2020/10/07/casey-macey-hertz/). In fact, I must acknowledge that Casey and Macey as well as Best Interest Blog inspired many of the ideas in this post.

Posted at 1:20 pm IST on Mon, 3 May 2021 permanent link

Archegos and marking academic literature to reality

Last week, Bill Hwang’s family office, Archegos, imploded as it was unable to meet the margin calls emanating from steep declines in the prices of stocks that Hwang had bought with huge leverage. Mark to market is a very powerful discipline that spares nobody however rich or powerful. This ruthless discipline makes financial markets self-correcting unlike many other social institutions.

Academic literature in particular is much more insulated from the discipline of mark to reality. Old papers discredited by subsequent developments or even subsequent research continue to be cited and quoted (this is the replication crisis in economics and finance). To borrow accounting terminology, the academic community tends to carry the old literature at historical cost without sufficiently stringent periodic impairment tests.

There is a large stream of finance and accounting literature which is probably badly impaired by last week’s developments. I refer to the literature that uses percentage of institutional shareholding in a company as a proxy for various things including corporate governance. What we are learning now is that Archegos used over the counter derivatives like swaps and contracts for differences to invest in a range of companies with very high leverage. The banks who sold these derivatives to Archegos bought shares in the companies to hedge the derivatives that they had sold. The shareholding pattern of these companies would then show the Archegos counterparties (banks) as the principal shareholders of these companies though in economic terms, the real owner of the shares was Archegos. Media reports suggest that this includes companies which were targeted by short sellers (and presumably had corporate governance concerns).

In the case of these companies with possibly dubious corporate governance, academics and investors might have been reassured on observing that say two-thirds of the shares were owned by institutions without realizing that much of the holding was the family office of a person who had committed insider trading. I think this is another illustration of Goodhart’s law: “Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.” The lesson that the academic literature must learn from that law is that the longer established a proxy measure is, the more ruthlessly one must apply an impairment test and mark it to reality.

Posted at 9:02 pm IST on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 permanent link

Stock Exchange Outages

A month ago, the National Stock Exchange (NSE), India’s largest stock exchange, suffered a software glitch and suspended trading about four hours prior to the scheduled end of the trading session. As the clock ticked close to the scheduled end of the trading day, there was no news about resumption of trading, and stock brokers decided to close out the outstanding positions of their clients on the other exchange (BSE) to avoid exposure to overnight price risk. About 13 minutes before scheduled close of the trading session, the NSE announced that normal market trading would resume 15 minutes after the scheduled close and would continue for 75 minutes thereafter. Yesterday, the NSE put out a self congratulatory press release providing some details of what happened on February 24, 2021. This is a vast improvement on the very limited information that they released a month ago (24th morning, 24th afternoon and 25th).

It appears that the regulators are also investigating the matter and, perhaps, much effort will be expended on apportioning blame between NSE and its various technology vendors. I wish to take a different approach here and argue that the regulators should simply lay down an downtime target. The computing industry works with Four Nines (99.99%) availability (less than an hour of downtime a year) and Five Nines (99.999%) availability (about five minutes of downtime a year). Let us assume that Five Nines is out of reach for stock exchanges and settle for Four Nines. There would then be no penalty for the first hour of downtime permitted under Four Nines and the penalty per hour thereafter would be calibrated so that the entire profits of the stock exchange are wiped out if the availability drops below Three Nines (99.9%) corresponding to a downtime of about nine hours per year.

Based on the most recent financial statements of the NSE, the penalty for that exchange would be about Rs 2.2 billion (around $30 million) per hour beyond the first hour. The penalty is designed to be large enough to ensure that the shareholders of the exchange weep when the exchange suffers an outage. They would then force the management to invest in technology, and also design management bonuses in such a way that they all get zeroed out when there is a large outage. The exchange would then negotiate large penalty clauses with their vendors so that if a telecom link fails, the telecom company pays a large penalty to the exchange. That provides the incentives to the telecom company to build redundancies. The regulators do not have to do any root cause analysis or apportion blame; they just have to collect the penalty, and use that to compensate the investors.

The other thing that the regulators need to do is to provide greater predictability about resumption of trading after a glitch. I would propose a simple set of rules here:

- If an exchange has suffered an outage and has not resumed trading one hour before the scheduled end of the trading session, all other exchanges (which have not suffered an outage) would extend their trading session by two hours automatically.

- If the exchange suffering the outage is able to resume trading not later than half an hour after the regular closing time, its trading session will also extend two hours beyond the regular closing time.

- If an exchange does not resume trading even half an hour after the scheduled closing time, it is not permitted to resume trading that day.

Stock exchange software glitches have been a favourite topic on this blog as long back as fifteen years ago and I suspect that they will continue to provide material for this blog for many, many years to come.

Posted at 5:07 pm IST on Tue, 23 Mar 2021 permanent link

Does Gamestop have a negative beta?

TL;DR: No!

The internet is a wonderful place: it knows that I have posted on Zoom’s negative beta and it also knows that I have posted on Gamestop and r/wallstreetbets. So it quite correctly concludes that I would have some interest in whether Gamestop has a negative beta. Yesterday, I received a number of comments on my blog on this question and my blog post also got referenced at r/GME. According to r/GME, several commercial sources (Bloomberg, Financial Times, Nasdaq) that provide beta estimates are reporting negative betas for Gamestop (GME).

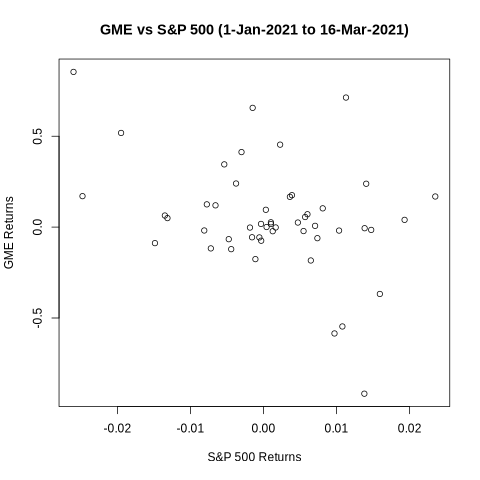

I began by running an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression of GME returns on the S&P 500 returns. Using data from the beginning of the year till March 16, I obtained a large negative beta which is statistically significant at the 1% level. (If you wish to replicate the following results, you can download the data and the R code from my website).

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

beta -10.54182 3.84200 -2.744 0.00851

The next step is to look at the scatter plot below which shows points all over the space, but does give a visual impression of a negative slope. But if one looks more closely, it is apparent that the visual impression is due to the two extreme points: one point at the top left corner showing that GME’s biggest positive return this year came on a day that the market was down, and the other point towards the bottom right showing that GME’s biggest negative return came on a day that the market was up. These two extreme points stand out in the plot and the human eye joins them to get a negative slope. If you block these two dots with your fingers and look at the plot again, you will see a flat line.

Like the human eye, least squares regression is also quite sensitive to extreme observations, and that might contaminate the OLS estimate. So, I ran the regression again after dropping these two dates (January 27, 2021 and February 2, 2021). The beta is no longer statistically significant at even the 10% level. While the point estimate is hugely negative (-5), its standard error is of the same order.

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

beta -4.97122 3.62363 -1.372 0.177

However, dropping two observations arbitrarily is not a proper way to answer the question. So I ran the regression again on the full data (without dropping any observations), but using statistical methods that are less sensitive to outliers. The simplest and perhaps best way is to use least absolute deviation (LAD) estimation which minimizes the absolute values of the errors instead of minimizing the squared errors (squaring emphasizes large values and therefore gives undue influence to the outliers). The beta is now even less statistically significant: the point estimate has come down and the standard error has gone up.

Estimate Std.Error Z value p-value

beta -2.7999 5.0462 -0.5548 0.5790

Another alternative is to retain least squares but use a robust regression that limits the influence of outliers. Using the bisquare weighting method of robust regression, provides an even smaller estimate of beta that is again not statistically significant.

Value Std. Error t value

beta -1.5378 2.3029 -0.6678

Commercial beta providers use a standard statistical procedure on thousands of stocks and have neither the incentive nor the resources to think carefully about the specifics of any situation. Fortunately, each of us now has the resources to adopt a DIY approach when something appears amiss. Data is freely available on the internet, and R is a fantastic open source programming language with packages for almost any statistical procedure that we might want to use.

Posted at 2:47 pm IST on Wed, 17 Mar 2021 permanent link

The rationality of r/wallstreetbets

Much has been written about how a group of investors participating in the sub-reddit r/wallstreetbets has caused a surge in the prices of stocks like GameStop that are not justified by fundamentals. I spent a fair amount of time reading the material that is posted on that forum and am convinced that most of these Redditors are perfectly rational and disciplined investors, and have no delusions about the fundamentals of the company.

Rationality in economics requires utility maximization, but does not constrain the nature of that utility function. It does not demand that the goals be rational as perceived by somebody else. Rationality of goals is the province of religion and philosophy: for example, Plato’s Form of the Good, Aristotle’s Highest Good, Hinduism’s four proper goals (puruṣārthas), and Buddhism’s right aspiration (sammā-saṅkappa). Economics concerns itself only with the efficient attainment of whatever goals the individual has. Even the Stigler-Becker maximalist view of economics (Stigler, G.J. and Becker, G.S., 1977. De gustibus non est disputandum. The American Economic Review, 67(2), pp.76-90) does not seek to impose our goals on anybody else, and does not require that the goals be pecuniary in nature (consider, for example, the Stigler-Becker discussion about music appreciation).

It is perfectly consistent with economic rationality for a person to buy a Tesla car as a status symbol and not as a means of going from A to B. Equally, it is perfectly consistent with economic rationality for a person to buy a Tesla share as a status symbol and not as a means of earning dividends or capital gains. Buddha and Aristotle might take a dim view of such status symbols, but the economist has no quarrel with them.

It is in this light that I find the Redditors at r/wallstreetbets to be highly rational. There is a clear understanding and Stoic acceptance of the consequences of their investment decisions. In this sense, there is greater awareness and understanding than in much of mainstream finance. When Redditors knowingly pay prices far beyond what is justified by fundamentals in the pursuit of non pecuniary goals, they are only indulging in a more extreme form of the behaviour of an environment conscious investor who knowingly buys a green bond at a low yield.

There is overwhelming evidence throughout r/wallstreetbets that these Redditors are focused on non pecuniary goals:

/r/wallstreetbets is a community for making money and being amused while doing it. Or, realistically, a place to come and upvote memes when your portfolio is down.

Yo, health check time: Get proper sleep, Eat proper food, Stretch occasionally, HYDRATE. I’m sure we’ve all been glued to our screens all week, but please make sure you take care of yourselves.

There is a crystal clear understanding that most trades will lose money:

Buy High Sell low - what you do as a newcomer.

First one is free - A phenomena where you are so retarded and don’t know what the [expletive deleted] your doing you somehow make money on your first trade.

… if you don’t know any of this there is really no reason for you to be throwing 10k at weeklies you’ll lose 99% of the time.

We don’t have billionaires to bail us out when we mess up our portfolio risk and a position goes against us. We can’t go on TV and make attempts to manipulate millions to take our side of the trade. If we mess up as bad as they did, we’re wiped out, have to start from scratch and are back to giving handjobs behind the dumpster at Wendy’s.

… and also for the most part, they’re playing with their own money that they can actually afford to lose even if it hurts for a year or two.

Options are like lottery tickets in that you can pay a flat price for a defined bet that will expire at some point.

Indeed mainstream regulators could borrow some ideas from r/wallstreetbets on how to disclose risk factors in an offer document. When a risky company does an IPO, a prominent disclosure on the front page “This IPO was created for you to lose money” would be far better than the pages and pages of unintelligible risk factors that nobody reads.

Posted at 8:19 pm IST on Sun, 31 Jan 2021 permanent link

SPACs and Capital Structure Arbitrage

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) have become quite popular recently as an attractive alternative to Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) for many startups trying to go public. Instead of going through the tortuous process of an IPO, the startup just merges into a SPAC which is already listed. The SPAC itself would of course have done an IPO, but at that time it would not have had any business of its own, and would have gone public with only the intention of finding a target to take public through the merger. Both seasoned investors and researchers take a dim view of this vehicle. Last year, Michael Klausner and Michael Ohlrogge wrote a comprehensive paper (A Sober Look at SPACs) documenting how bad SPACs were for investors that choose to stay invested at the time of the merger. Smart investors avoid losses by bailing out before the merger, and the biggest and smartest investors make money by sponsoring SPACs and collecting various fees for their effort.

As I kept thinking about the SPAC structure, it occurred to me that at the heart of it is a capital structure arbitrage by smart investors at the cost of naive investors. The capital structure of the SPAC prior to its merger consists of shares and warrants. However, in economic terms, the share is actually a bond because at the time of the merger, the shareholders are allowed to redeem and get back their investment with interest. It is the warrant that is the true equity. If the share were treated as equity, it would have a lot of option value arising from the possibility that the SPAC might find a good merger candidate, and the greater the volatility, the greater the option value. A part of the upside (option value) would rest with the warrants. But if the shares are really bonds, then all the option value resides in the warrants which are the true equity. Naive investors are perhaps misled by the terminology, and think of the share as equity rather than a bond; hence, they ascribe a significant part of the option value to the shares. Based on this perception, they perhaps sell the detachable warrants too cheap, and hold on to the equity.

From the perspective of capital structure arbitrage, this is a simple mispricing of volatility between the two instruments. Volatility is underpriced in the warrants because only a part of the asset volatility is ascribed to it. At the same time, volatility is overpriced in the shares since a lot of volatility (that rightfully belongs to the warrant) is wrongly ascribed to the share. One way for smart investors in SPACs to exploit this disconnect is to sell (or redeem) the share and hold onto the warrant, while naive investors hold on to the share and possibly sell the warrant.

Capital structure arbitrage suggests a different (smarter?) way to do this trade. If at bottom, the SPAC conundrum is a mispricing of the same asset volatility in two markets, then capital structure arbitrage would seek to buy volatility where it is cheap and sell it where it is expensive. In other words, buy warrants (cheap volatility) and sell straddles on the share (expensive volatility). At least some smart investors seem to be doing this. A recent post on Seeking Alpha mentions all three elements of the capital structure arbitrage trade: (a) sell puts on the share, (b) write calls on the share and (c) buy warrants. But because the post treats each as a standalone trade (possibly applied to different SPACs), it does not see them as a single capital structure arbitrage. Or perhaps, finance professors like me tend to see capital structure arbitrage everywhere.

Posted at 4:51 pm IST on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 permanent link

Disappointing Investigation Report on London Capital & Finance

Earlier this month, the United Kingdom Treasury published the Report of the Independent Investigation into the Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA’s) Regulation of London Capital & Finance (LCF). I read it with high expectations, but must say I found it deeply disappointing. I take perverse pleasure in reading investigation reports into frauds and disasters around the world (so long as they are in English). Beginning with Enron nearly two decades ago, there have been no dearth of such high quality reports except in my own country where unbiased factual post mortem reports are quite rare. So it was with much anticipation that I read the report on LCF which involved a number of novel issues about the risk posed by unregulated businesses carried out by regulated entities. Unfortunately, the Investigation Report did not meet my expectations: instead of providing an unbiased and dispassionate analysis of what happened, it indulges in indiscriminate and often unwarranted criticism of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). In the process, the report very quickly loses all credibility.

The LCF debacle is described well in the report of the Joint Administrators under the Insolvency Act from which this paragraph is drawn. LCF was set up in 2012 as a commercial finance provider to UK companies. From 2013, the Company sold mini-bonds, with trading significantly increasing from 2015 onwards. LCF was granted “ISA Manager” status by the UK taxation authorities (HMRC) in 2017, and LCF started selling its mini bonds under this rubric. (The necessary requirements to qualify for ISA Manager status are fairly limited; it is not a rigorous application process; and ISA Managers are not routinely monitored by HMRC). About 11,500 bond holders invested in excess of £237m in LCF mini bonds. The vast majority of LCF’s assets are the loans made to a number of borrowers a large number of whom do not appear to have sufficient assets with which to repay LCF. At present the Administrators estimate a return to the Bondholders from the assets of the Company of as low as 20% of their investment.

It is evident from the above that the most important issue in the LCF debacle is a failure of regulation rather than supervision. In the UK, mini bonds (illiquid debt securities marketed to retail investors) are subject to very limited regulation unlike in many other countries. (In India, for example, regulations on private placement of securities, collective investment schemes and acceptance of deposits severely restrict marketing of such instruments to retail investors). To compound the problem, the UK allows mini bonds to be held in an Innovative Finance ISA (IFISA). ISAs (Individual Savings Accounts) are popular tax sheltered investment vehicles for retail investors. The UK has taken a conscious decision to allow these high risk products to be sold to retail investors in the belief that the benefits in terms of innovation and financing for small enterprises outweigh the investor protection risks. While cash ISAs and Stock and Share ISAs are eligible for the UK’s deposit insurance and investor compensation scheme (FSCS), IFISAs are not eligible for this cover. Many investors may think that ISAs are regulated from a consumer protection perspective, but the UK tax department thinks of approval of ISAs as purely a taxation issue. To make matters worse, the UK has had extremely low interest rates ever since the Global Financial Crisis, and yield hungry investors have been attracted to highly risky mini bonds especially when they are marketed to retail investors under the veneer of a quasi regulated product - the IFISA. After the LCF debacle, some regulatory steps have been taken to alleviate this problem.

The Investigation Report is concerned about supervision more than regulation, and here the key issue is the regulatory perimeter issue: when an entity carries out a regulated business and an unregulated business, to what extent should the regulators examine the unregulated business. There are some financial businesses like banking where there is intrusive regulation of the unregulated business (the bank holding company). But what should the regulatory stance be on small regulated entities that carry out very limited regulated businesses (for example, confined mainly to financial marketing)? The Investigation Report simply points to the regulatory powers of the FCA to look at the unregulated business, and blithely asserts that the FCA should have been doing this routinely. This is unrealistic and would confer excessive and unacceptable powers to the financial regulators that would make them overlords of the entire society. Imagine that the publisher of the largest circulation newspaper in the country also publishes an investment newsletter that could be construed as financial promotions and is therefore regulated by the financial regulators. Do we want the regulator to have the power to take some regulatory action because it does not like the editorial stance of the newspaper? If you think that I am insane to consider such possibilities, you should examine the criminal prosecution that German financial regulators launched against two Financial Times journalists for its reporting on the Wirecard fraud. The Investigation Report does not reveal any such nuanced understanding and therefore represents a missed opportunity to improve our perspective on such matters.

Since the issuance of mini bonds is itself not a regulated activity, the role of the FCA is mainly in the area of the marketing of the bonds by LCF as a regulated entity authorized to carry on credit broking and some corporate finance activities. I would have expected the Investigation Report to focus on whether the FCA monitored LCF’s marketing (financial promotions) adequately. The Investigation Report documents that FCA received a few complaints on this, and in each instance, the FCA required changes in the website to conform to the FCA requirements. In my understanding, it is quite common for regulators worldwide to require changes in the financial promotions ranging from the font size and placement of a statement to changes in wordings to more substantive issues. The question that is of interest is where did LCF breaches lie on this spectrum (some of them were clearly technical breaches) and how did the frequency of serious breaches compare with that of other entities of similar size that the FCA regulates. Unfortunately, the Investigation Report does not provide an adequate analysis of this matter, other than saying that repeat breaches should have led to severe actions including an outright ban on LCF. That is not how regulation works or is expected to work anywhere in the world.

But these two inadequacies of analysis are not the main grounds for my disappointment with the Investigation Report. What troubled me is the repeated instances of what struck me as prima facie evidence of bias. At first, I brushed these aside and kept reading the report with an open mind, but slowly, the indicia of bias kept piling up and I began to question the objectivity and credibility of the report. At every twist and turn, wherever there was a grey area, the Investigation Report unfailingly ended up resolving this against the FCA. In the process, the credibility of the report was eroded bit by bit. By the time, I reached the end, the credibility of the report had been completely destroyed.

One of the most glaring examples of apparent bias is the discussion about a letter purported to have been sent by one Liversidge to the FCA. The only evidence for this is the statement by Liversidge that he did post the letter. Detailed search of all records at the FCA failed to find any evidence that the letter was in fact received by the FCA. One of the first things that is taught in all basic courses on logic is that it is impossible to prove a negative statement (like the statement that the letter was not received) and that is essentially what the FCA quite honestly told the Investigation Team. The Investigation Report first states that whether this letter was received or not is not relevant to the Investigation. That should have been the end of the matter. But then it goes on to make the statement that “if it had been incumbent on the Investigation to have reached a decision on this point, it would have concluded on the balance of probabilities that the Liversidge Letter was received by the FCA”. This is unreasonable in the extreme: there is no evidence other than the sender’s testimony that the letter was sent at all (let alone received), while there is some evidence that it was not received. The balance of probabilities clearly points the other way.

The Report goes to great lengths to criticize the FCA for the extended timelines of the DES programme which attempted a very significant transformation in the structure, the governance, the systems, the processes, the risk frameworks of supervision at the FCA. This was initiated around end of 2016 or early 2017 with a target completion date of March 2018, but was concluded only by December 2018. Having been involved in exercises of this kind in many organizations, I think spending a couple of years to accomplish something like this is quite reasonable (In fact it strikes me as a rather aggressive timeline). The original timeline of March 2018 appears to me to have been utterly unrealistic. The Investigation Report suggests that the FCA should instead have resorted to some “quick wins, reviews or easy fixes”. I think this suggestion is utterly misguided. “Easy fixes” is precisely the kind of thing that an organization should not do under such conditions. I think it is to the credit of the FCA Board that it did not undertake such a stupid course of action.

Actually, the FCA discovered the fraud on its own from two different angles. First, LCF filed a prospectus with the FCA and the Listing Team had a number of serious concerns on this. Second, during the course of a review of an external database (only accessible to a limited group within the FCA and on strict conditions of use) concerned with another firm, the Intelligence Team found some information on LCF and immediately escalated the matter. While the Investigation Report commends these actions, it states that if other employees at the FCA had similar levels of expertise in understanding financial statements, they would have uncovered the fraud earlier. I was aghast on reading this. Expertise in financial statements is a highly sought skill that is in short supply in the market. That the FCA manages to hire people with that skill in some critical departments is great. To expect that people in the call centre or those running authorizations would have this skill is absurd. If people with such skills thought that they may be transferred to such postings, they would probably not join the FCA in the first place.

The Investigation Report finds fault with the FCA for giving LCF permissions to carry out regulated businesses that it did not in fact use. I do not find this unusual at all. To give an analogy, the objects clause in the corporate charter (Memorandum of Association) typically contains a lot of things that the company has no intention of undertaking; it includes these things because of the severe consequences of finding that the company does not have the power under its charter to do something that has suddenly become desirable. Similarly, a regulated business would often want to have a range of regulatory authorizations that it does not expect to use. All the more so because regulators often take an restrictive view of things and take companies to task for all kinds of technical violations. For example, a stock broker who provides only execution services might want to have an advisory licence to guard against the risk that some incidental service that it provides could be regarded as advisory. Similarly, an advisory firm might worry that a minor service like collecting a document from the customer and delivering it to a stock broker might be interpreted as going beyond purely advisory services. That LCF obtained a licence but did not carry out the regulated activity is not in my view a red flag at all. The Investigation Report makes a song and dance about this despite having observed one fact that demonstrates its triviality. The FCA created a system that produced an automated alert whenever a firm did not generate income from regulated activities. Because of the high volume of automated alerts that were created as a result of this, the FCA had to allow these alerts to be closed without review!

It is indeed distressing that this deeply flawed report is all that we will ever get on this episode which raises so many interesting regulatory issues of interest across the world.

Posted at 9:38 pm IST on Tue, 29 Dec 2020 permanent link

The value of financial centres redux

When I started this blog over 15 years ago, one of my earliest posts was entitled Are Financial Centres Worthwhile? The conclusion was that though the annual benefits from a financial centre appear to be meagre, they may perhaps be worthwhile because these benefits continue for a very long time as leading centres retain their competitive advantage for centuries. At least, most countries seemed to think so as they all eagerly tried to promote financial centres within their territories. But that was before (a) the Global Financial Crisis and (b) the current process of deglobalization.

Yesterday, the United Kingdom finalized the Brexit deal with the European Union, and the UK government rejoiced that they had got a trade deal without surrendering too much of their sovereignty. There was no regret about there being no deal for financial services. The UK seems quite willing to impair London as a financial centre in the pursuit of its political goals. China seems to be going further when it comes to Hong Kong. It has been willing to do things that would damage Hong Kong to a much greater extent than Brexit would damage London. Again political considerations have been paramount.

Decades ago, both these countries looked at financial centres very differently. After World War I, the UK inflicted massive pain on its economy to return to the gold standard at the pre-war parity. In some sense, the best interests of London prevailed over the prosperity of the rest of the country. Similarly during the Asian Crisis when Hong Kong’s currency peg to the US dollar seemed to be on the verge of collapse, then Chinese Zhu Rongji declared at a press conference that Beijing would “spare no efforts to maintain the prosperity and stability of Hong Kong and to safeguard the peg of the Hong Kong dollar to the U.S. dollar at any cost” (emphasis added). The major elements of that “at any cost” promise were (a) the tacit commitment of the mainland’s foreign exchange reserves to the defence of the Hong Kong peg, and (b) the decision not to devalue the renminbi when devalations across East Asia were posing a severe competitive threat to China. In some sense, the best interests of Hong Kong prevailed over the prosperity of the mainland.

Clearly, times have changed. The experience of Iceland and Ireland during the Global Financial Crisis demonstrated that a major financial centre was a huge contingent liability that could threaten the solvency of the nation itself. Switzerland was among the first to see the writing on the wall; it forced its banks to downsize by imposing punitive capital requirements. Other countries are coming to terms with the same problem. Deglobalization adds to the disillusionment about financial centres.

Today, countries are eager to become technology centres rather than financial centres. How that infatuation will end, only time will tell.

Posted at 7:43 pm IST on Fri, 25 Dec 2020 permanent link

Comments